Formative Feedback Strategies that Foster Learner Growth

04/01/2024

Formative feedback in medical education involves observing the trainee’s performance within a certain domain and comparing it against an expected standard. Formative feedback should be clear, specific, timely, actionable, and based on observed activity or behaviors.

In undergraduate medical education, the 13 AAMC core entrustable professional activities (Core EPAs) are one example of a structure for designing medical education curricula, providing formative feedback and creating expectations for trainees. Formative feedback allows educators to reinforce the importance of applying textbook knowledge and incorporating continued learning to improve patient care and health outcomes.

The Value of Formative Feedback

Well-constructed formative feedback allows learners to identify their areas of strength and opportunities for improvement. Specific formative feedback should focus on assessing competencies learned through training such as clinical skills, medical knowledge, decision-making processes, systems-based practices, communication or interpersonal interactions. Value for the learner includes development of a shared mental model, increased transparency in intended learning outcomes, and enhanced ability to self-assess and correct future performance.

There are numerous examples of formative feedback being impactful for learners. Importantly, patient safety concerns can arise at critical patient hand-off points, such as shift change between medical teams. The Association of American Medical Colleges' Core EPA 8, “give or receive a patient handover to transition care responsibility,” focuses on developing this skill set. Another demonstration of impact was implemented at two medical schools during the third year of medical school during students’ third and fourth clerkships. Students’ skills were observed and they received feedback utilizing a work-place based assessment form. Data from graduation surveys indicated that these students were more likely to report confidence in possessing the skills needed for safe handovers as compared to students at other institutions. Feedback, when specific and actionable, enhances the quality of medical education and helps develop skilled physicians who are well prepared to care for patients Another example includes fourth-year acting internship students who were provided feedback based on direct observation of their skills by faculty. There was notable improvement on skills evaluated based on the pre-post self-efficacy survey results.

Challenges and Opportunities in Feedback Delivery

Educators and learners face real and perceived challenges when delivering feedback in the clinical setting. These may include lack of direct observation of tasks, misperception, limited external feedback leading to learners formulating self-assessments subjectively, non-specific feedback, feedback delay, and improper setting. To overcome these challenges, it is important for educators to approach feedback systematically by utilizing an evidence-based feedback framework such as:

- Set SMART (specific, measurable, achievable, relevant, time-bound) goals. SMART goals allow the educator and the learner to work together, develop goals to improve skills, and provide feedback based on observation of the skills in a short time frame.

- Utilize Ask-Tell-Ask which involves the learner performing a self-reflection exercise, followed by the educator providing specific feedback. The learner is then asked about their understanding of the feedback received.

- Engage the RIME (reporter, interpreter, manager, educator) framework which provides a structure for evaluating a learner’s progression from basic to advanced level.

- Employ Pendelton’s Rules for Feedback, which is a five-step process in which the learner and educator both identify strengths and weaknesses starting with the learner’s perspective. The educator then summarizes improvement opportunities with the learner.

Educators must create an environment that supports the learner and sets the stage for feedback delivery. Feedback should be delivered in a non-threatening manner, fostering psychological safety. Feedback may, at times, be negative, which will require the learner to reflect upon the feedback, adjust, and work to improve their performance. Feedback should focus on skills and behavior and not be based on individual personality or characteristics. Diversity of experiences must be considered to avoid discrimination based on race, ethnicity, gender, and sexuality.

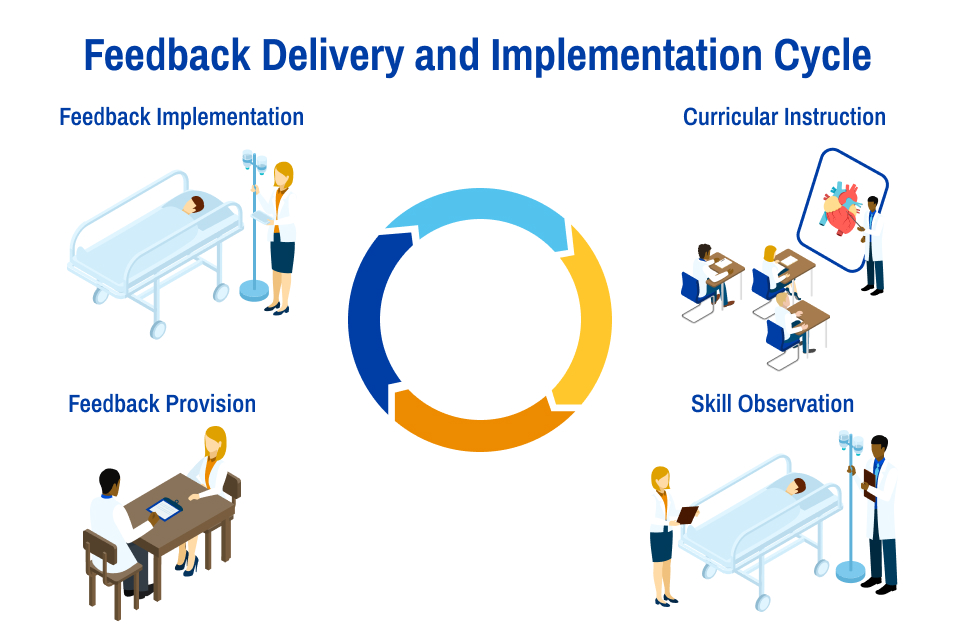

Supporting Effective Feedback Delivery and Implementation

Feedback is most effective when it is a two-way conversation between the learner and the educator, ideally forming an educational alliance. Learners should actively seek feedback, and implementation should be approached with a growth mindset. Self-reflection is also essential and can be formal or informal but should be consistent during the learning phases. As an example, consider a learner tasked with seeing a new patient in the emergency room. Their history-taking skills are observed by the clinician-educator. The learner is asked to reflect on the conversation and identify areas in which they could have asked the patient to expand on their symptoms to obtain a more thorough understanding of the chief complaint. Learners should then apply the formative feedback through goal setting, seeking further mentorship, and additional reflection exercises.

In sum, feedback is integral to the development of a well-rounded physician. While there is great emphasis on objective measures of knowledge such as examination performance and board scores, it is important that clinical skills are taught and evaluated on a routine basis in the clinical setting. A culture of continuous feedback, with a focus on the growth mindset, is essential to the development of physicians and is beneficial to the overall healthcare system. The practice of delivering formative feedback requires an understanding of the learners’ and educators’ perspectives. We must be flexible and open to incorporating new techniques to improve feedback delivery through continuous learning and engagement.

Keniesha Thompson, M.D., is associate professor of Internal Medicine and assistant dean of Student Affairs at SSM Health and the Saint Louis University School of Medicine. Thompson holds a Master of Science in Outcomes Research and Evaluation Sciences, is a fellow of the American College of Physicians, and is a fellow of the Society of Hospital Medicine. Thompson's areas of professional interest include quality improvement, career discernment, and the support of learners from disadvantaged backgrounds. Thompson can be found on LinkedIn or contacted via email.